The following is the first of a two-part article.

The reporting on the Sago Mine tragedy in West Virginia followed a predictable pattern: superficial interviews with families of survivors, expressions of sympathy, and the affirmation that everyone will pull together and carry on.

Before packing up their cameras and ending their coverage of the mine disasters, the news media presented conditions in the Appalachian coalfields as an unchanging fact of life. Lack of jobs, low wages and dangerous working conditions are presented as a fixture in the mountains of West Virginia, as inevitable as the succession of the seasons.

A piece in USA Today was fairly typical. “Despite tragedy, miners’ way of life will live on,” the headline reads. We are told that following these deaths, things will continue on as always because “Coal mining is a lifestyle and a family tradition.”

This point of view is not only patronizing to the degree of open contempt, it is at odds with reality. What it leaves out is the fact that the coal miners for more than a century have been in the forefront of the struggles of the American working class for progressive social change. Far from adapting themselves to the “lifestyle” described by the media, the miners have again and again waged bitter and often bloody rebellions against the coal operators and their agents in the state and federal government.

Coal continues to be a critical energy source for US capitalism. Its importance is again being heightened by the military debacle in Iraq and the rise in world oil prices. The ability to extract this resource at low costs competitive on the world market is crucial for coal mine owners and American big business as a whole.

The ruling elite and its media servants react nervously and with hostility to any signs of renewed militancy among this key section of the working class. Above all, they try to cut off the working class and, in particular, the younger generation, from any knowledge of their own history.

Coal miners were among the first sections of the American working class to organize in unions. From the days of the Molly Maguires in the Pennsylvania anthracite coalfields in the 1870s to Matewan and the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1920-1921, the coal miners have replied in kind to the violence and repression directed against them by the mine owners and their private gunmen. In these and other conflicts, the intensity of industrial struggles involving the coal miners sometimes bordered on civil war.

In the 1930s, the miners’ union provided the organizing base for the construction of the mass industrial union movement in the United States, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Despite retreats and setbacks, the struggles of the miners ultimately culminated in the unionization of virtually the entire US coalfields. Before and during the Second World War, coal miners launched two major strikes and defied the ferocious attacks of big business and the Roosevelt administration, which was demanding that labor leaders place the unions fully behind the war effort.

In the immediate post-World War II period, substantial improvements were made in wages, pensions, health and safety. When Congress ordered hundreds of thousands of miners back to work under the newly passed Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, the miners defiantly declared, “Let the Senators dig coal.” In 1952, a mine safety act was passed, after an explosion that killed 119 miners in West Frankfurt, Illinois, that for the first time established a federal role in mine safety.

However, the improvements won by miners were quickly eroded as the coal industry entered an extended depression during the decade of the 1950s, as coal prices plummeted and the mine owners used new mining machinery to increase productivity and eliminate hundreds of thousands of jobs. Between 1950 and 1960, employment in coal mining fell from 488,000 to 166,000. Many of those who remained in the mines were working part-time and were barely able to feed their families.

The organization built by the miners, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), proved unable to respond to this change in a progressive fashion. UMWA President John L. Lewis, who had led the formation of the CIO in the 1930s and had called numerous nationwide coal strikes, capitulated to the owners’ demands for layoffs and cost savings.

The resulting social catastrophe in the Appalachian mining region was a stark demonstration of the inability of trade unions based on a pro-capitalist and nationalist perspective to defend the interests of the working class. Lewis rejected demands for measures, such as a shorter workweek, to shift the burden of the crisis onto the backs of the employers. Instead, he sought to work with the operators to drive up profits through squashing militancy and eliminating “surplus” labor. After 1950, he never again called another nationwide contract strike. He even offered to help owners purchase more-efficient mining equipment through exempting them from payments to the union’s health and welfare fund.

The destruction of mining jobs and the deterioration of overall social conditions forced the emigration of hundreds of thousands of impoverished workers and their families from the mining areas to big cities in the Midwest, where they often encountered discrimination.

In 1960, West Virginia’s poverty rate stood at 31 percent. Many homes lacked basic amenities such as indoor plumbing. Thousands of miners were condemned to early deaths due to black lung disease, which was not officially recognized as an occupational illness. The levels of social deprivation in the area were only comparable to the most impoverished inner city ghettos.

The conditions in Appalachia became a national scandal. Michael Harrington in his book The Other America: Poverty in the United States, published in 1962, described these conditions. “During the decade of the 1950s, 1,500,000 people left the Appalachians.... Those who were left behind tended to be the older people, the less imaginative, the defeated. One reporter wrote: ‘Whole counties are precariously held together by a flour-and-dried milk paste of surplus foods. The school lunch program provides many children with their only decent meals. Relief has become a way of life for a once proud and aggressively independent mountain people. The men who are no longer needed in the mines and the farmers who cannot compete with the mechanized agriculture of the Midwest have themselves become surplus commodities in the mountains.’ ”

The struggle against Boyle

After Lewis retired in 1960, the leadership of the UMWA passed briefly into the hands of Thomas Kennedy and then to Tony Boyle, a Lewis favorite, whose administration became notorious for its gangsterism and corruption. Boyle’s regime collaborated openly with the coal operators, leading to growing rank-and-file opposition.

In 1968, an explosion ripped through a Consolidation Coal mine in Farmington, Virginia, killing 78 miners. All those trapped inside the mine died, including 19 whose bodies were never recovered. Boyle demonstrated his contempt for the men he supposedly represented when in the wake of the tragedy he declared, “Coal mining always brings with it an inherent danger of explosion.”

In 1968, an explosion ripped through a Consolidation Coal mine in Farmington, Virginia, killing 78 miners. All those trapped inside the mine died, including 19 whose bodies were never recovered. Boyle demonstrated his contempt for the men he supposedly represented when in the wake of the tragedy he declared, “Coal mining always brings with it an inherent danger of explosion.”

Following the Farmington tragedy, anger over health and safety issues and the collusion of the Boyle leadership with management boiled over. One expression of this was the organization by rank-and-file miners with the aid of sympathetic medical professionals of the Black Lung Association to press for legislation making black lung disease a compensable illness. On Feb 18, 1969, miners in West Virginia launched a 23-day wildcat strike to demand enactment of a black lung bill stalled in the state legislature. The strike forced the passage of the bill, the first such legislation relating to black lung in the United States.

The movement of the miners along with growing public outrage over conditions in the mines combined to force passage later in 1969 of the federal Mine Safety and Health Act, despite a threatened veto by President Nixon. The bill prescribed safety measures to prevent cave-ins and explosions, mandated regular safety inspections and set legal limits on the amount of coal dust. At the same time, hospitals and black lung clinics funded by the company-paid health and retirement fund were built throughout the coalfields, giving miners and their families, in many cases, access to such facilities for the first time.

However, in practice, enforcement of safety regulations and health improvements continued to take a backseat to the profit requirements of the coal operators. In February 1972, a dam impounding a coal slurry pond collapsed in Logan County, West Virginia, killing 125 people and making another 4,000 people homeless. Survivors of the Buffalo Creek flood sued the Pittston Coal Company, which owned the dam, but collected only a pittance in compensation. No mine officials were ever prosecuted, even though Pittston had blatantly violated federal safety standards.

Meanwhile, opposition to the Boyle leadership found expression in the candidacy of former District 5 official Jock Yablonski. In 1969, Yablonski lost a closely contested race to Boyle for the UMWA presidency. Yablonski’s supporters claimed the election was rigged and challenged the results. A short while later, Yablonski, his wife and daughter were found murdered in their home in Clarkesville, Pennsylvania.

This gangster-style killing did not intimidate the miners; instead, it further inflamed their anger. The day after the killing, miners in West Virginia walked off the job in protest. A rank-and-file opposition called Miners for Democracy took shape. Its candidate Arnold Miller, running under the slogan, “Coal will be mined safely or not at all,” defeated Boyle in a 1972 election supervised by the US Labor Department. Shortly afterward, Boyle was convicted of ordering the murder of Yablonski and sentenced to life in prison. Whether or not Boyle was guilty of this particular crime, rank-and-file miners did not doubt that he was capable of such a bloody act.

The movement against Boyle coincided with a temporary upsurge in coal production. In the early 1970s, thousands of mining jobs were added. Miners took the ouster of Boyle as a signal to go on the offensive. Thousands of miners struck in Illinois over the issue of safety. In Harlan County, Kentucky, long an anti-union bastion, miners waged a successful 13-month strike for union recognition at the Brookside mine.

The movement against Boyle coincided with a temporary upsurge in coal production. In the early 1970s, thousands of mining jobs were added. Miners took the ouster of Boyle as a signal to go on the offensive. Thousands of miners struck in Illinois over the issue of safety. In Harlan County, Kentucky, long an anti-union bastion, miners waged a successful 13-month strike for union recognition at the Brookside mine.

Upsurge in the 1970s

This was a period of militant trade union struggles against the attempt of the Nixon administration to shift the cost of the war in Vietnam onto the backs of the working class, culminating in President Nixon’s decision in August 1971 to remove the gold backing from the US dollar, ushering in a period of mounting economic turmoil. It marked the beginning of an offensive by US capitalism against the working class that continues to the present day. The working class responded with increasingly militant struggles. However, the leadership of the unions moved in the opposite direction, toward policies of open collaboration with the corporate bosses.

From the beginning, the upsurge of the miners in the 1970s collided with the leadership of Miller, who had been helped into office by the US government under conditions in which the discredited Boyle leadership could no longer control the ranks. Miller maintained the subordination of the union to the Democratic Party, which meant the effective subordination of the miners to the interests of corporate America. In West Virginia, the alliance with the Democrats meant the union was committed to working hand in hand with direct political representatives of the mine bosses.

In August 1974, the UMWA called a five-day “memorial period,” and thousands of miners marched on Washington to demand the ouster of James Day, a Republican Party aide who headed the US Mining Enforcement and Safety Administration. Day later resigned.

Just three months later, in November 1974, the UMWA called a national contract strike involving 120,000 miners. Twice, the UMWA bargaining council rejected sellout contracts accepted by Miller. Ultimately, the miners were saddled with an agreement that imposed a two-tier pension agreement, which passed by a narrow 56 percent margin. Older retirees would be forced to continue drawing lower benefits under the old 1950 pension fund that had been bankrupted by Lewis and Boyle.

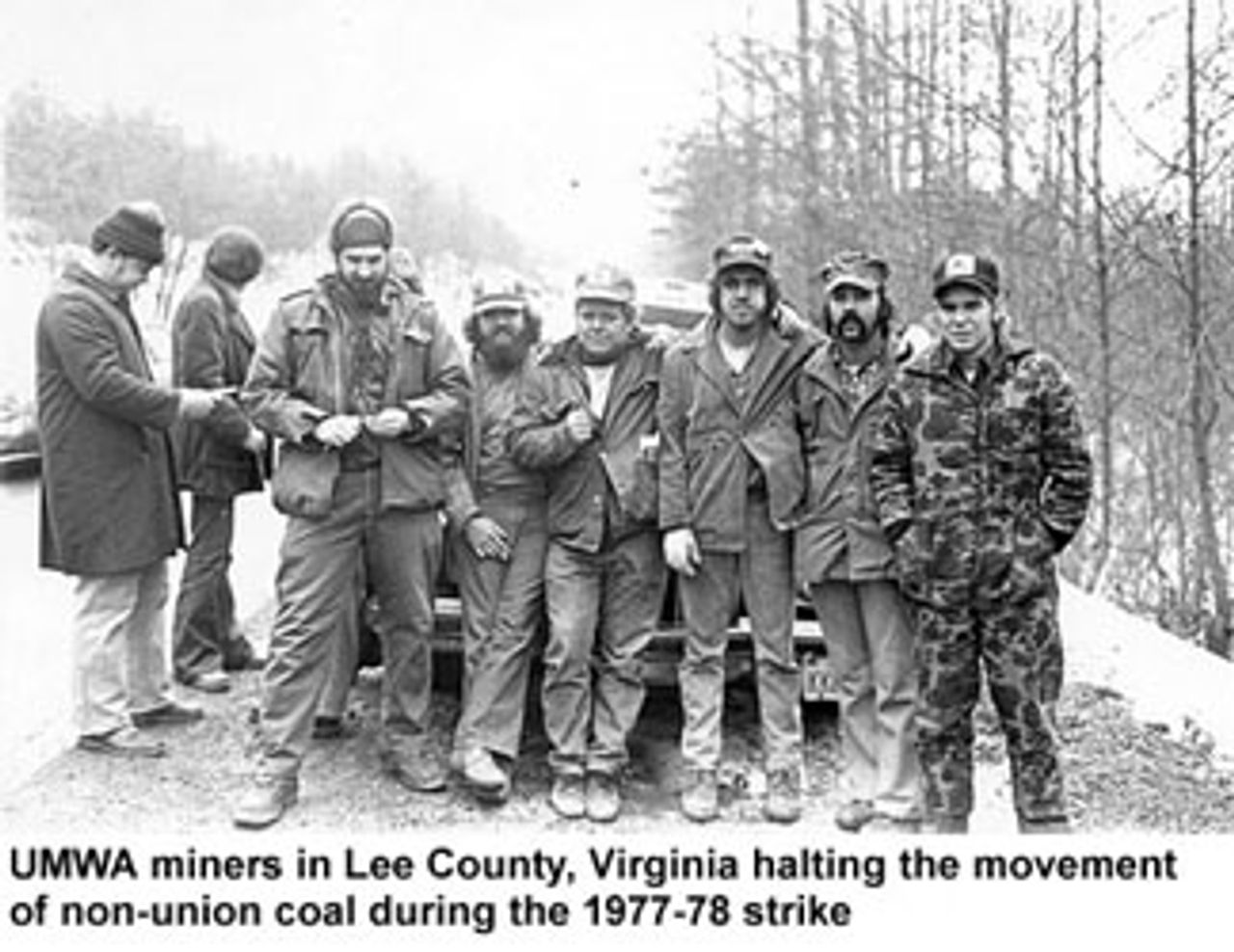

Anger over the sellout was reflected in wildcat strikes and militant action over the next three years, culminating in the record 111-day contract strike between December 1977 and March 1978 and the defiance by the miners of a strikebreaking Taft-Hartley injunction imposed by Democratic President Jimmy Carter.

Anger over the sellout was reflected in wildcat strikes and militant action over the next three years, culminating in the record 111-day contract strike between December 1977 and March 1978 and the defiance by the miners of a strikebreaking Taft-Hartley injunction imposed by Democratic President Jimmy Carter.

Carter intended to deal a defeat to the miners in the interests of his energy policy, which was based on substituting coal for imported oil. For this to be successful, the cost of coal production had to be driven down, which meant increasing the rate of exploitation in the mines. The attack on the miners was aimed essentially at the entire American working class, which was carrying out militant strikes in auto, steel, rubber, aerospace and other basic industries against the attempts of big business to use inflation to slash living standards.

Carter intended to deal a defeat to the miners in the interests of his energy policy, which was based on substituting coal for imported oil. For this to be successful, the cost of coal production had to be driven down, which meant increasing the rate of exploitation in the mines. The attack on the miners was aimed essentially at the entire American working class, which was carrying out militant strikes in auto, steel, rubber, aerospace and other basic industries against the attempts of big business to use inflation to slash living standards.

The miners spread the walkout across the coalfields, shutting down union and nonunion mines alike. Democratic “friends of labor” such as West Virginia Governor Jay Rockefeller mobilized hundreds of state police and National Guard troops against the miners. Three miners were killed during the first two months of the strike, and hundreds were arrested.

Twice, rank-and-file miners mobilized to defeat sellout contracts accepted by Miller. On March 6, Carter declared an emergency and ordered the miners back to work under provisions of the anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act. Carter’s intervention was a watershed event, which underscored the bankruptcy of the UMWA’s and AFL-CIOs’ alliance with the Democratic Party as an alliance with strikebreakers. It also demonstrated the rottenness of the entire AFL-CIO bureaucracy, which lined up behind Carter in support of a return to work.

Rank-and-file miners, however, ignored the injunction and continued their strike. Ultimately, the Carter administration had to rely on the Miller bureaucracy to force an end to the walkout. The UMWA leadership finally succeeded in pushing through a contract imposing substantial concessions. Among the methods employed by the UMWA bureaucracy to browbeat the rank-and-file was the withholding of millions of dollars in strike-support money from the financially strapped strikers.

While the miners were able to maintain certain gains in wages, as a result of the strike they lost their 100 percent medical coverage. The mine owners were also able to retain the hated two-tier pension.

However, the strike, which was followed by workers in the US and throughout the world, had shaken the Carter administration and the entire Washington and Wall Street establishment. The miners’ successful defiance of Carter exposed the weakness and impotence of his administration and underscored its inability to inflict a decisive defeat on the working class.

Anger at Miller’s sellout led to his resignation in 1979. He was replaced by UMWA Vice President Sam Church who continued Miller’s policies. In 1981, another national contract strike was called and ended in a sellout by the Church leadership after 72 days. It was the last nationwide contract strike called by the UMWA.

To be continued