HITLER: We are not ready for this turn of affairs. You have completely bungled the work you were supposedly directing with judicious ability…. You are trying to force us to act in Russia before we are ready!

TROTSKY: No, no, Herr Hitler. This is an unfortunate accident. You know I am in perfect accord with your plans.1

The above extract comes from a screenplay treatment by Erskine Caldwell for the Warner Brothers pro-Stalin propaganda film Mission to Moscow (1943), in which the devious head of the Fourth International conspires with Hitler, von Ribbentrop, Goebbels and Hess in the Führer’s Bavarian hideaway to overthrow the Soviet government with the aid of the future Moscow trial victims.

Neither this scene nor Howard Koch’s revised scene placing an “intense and agitated”2 Trotsky in the German Embassy in Norway with von Ribbentrop and the German ambassador, Heinrich Sahm, thankfully appear in the final film. Koch describes the meeting: “The Germans retain a surface politeness, but underneath this manner is condescension and contempt for the exiled Russian conspirator.”3 Realizing that no support will be forthcoming from the Third Reich, Trotsky departs after an ignominious outburst. “But what about me? What am I to do in the meantime? My following in Russia will fall away.”4 Trotsky does not appear in the final version.

Naturally, the founder of the Fourth International could not for the most part be expected to find a positive cinematic representation in the world of either Western or Eastern (Stalinist) film and television, which had their own political agendas.

In the 1963 75-minute BBC TV Wednesday Play “The Executioner,” Trotsky is played off-camera by the veteran character actor Meir Tzelniker in a narrative focusing on his tortured assassin Ramon Mercader, played by 1956 Hungarian revolt refugee Sandor Eles. Mercader exists in a tormented pre-Oedipal relationship with his mother (Rosalie Crutchley), who is sleeping with KGB agent Leonid Eitingon. The Stalinist assassin resembles a post-Psycho version of Norman Bates more than the devious figure who wormed his way into Trotsky’s confidence.

In Franklin J. Schaffner’s Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), Brian Cox plays Trotsky both as a young man and as the key force later behind the Russian Revolution. Naturally, this Hollywood-influenced biopic has its own share of problems, such as having Trotsky and Stalin meet (“My name’s Trotsky. What’s yours?” “Stalin.” “Pleased to meet you”) at the 1903 London conference of the Russian Social Democratic Party, a gathering that the future “Great Leader” never attended, but it does show disagreements between Trotsky and Lenin (Michael Bryant) at an earlier stage of their relationship that the film depicts in a serious fashion.

Despite central prominence in Joseph Losey’s Italian-French co-production The Assassination of Trotsky (1972), the figure of Trotsky in that film bears little resemblance to his real-life self. Played by Richard Burton in a film containing weak performances by Alain Delon and Romy Schneider, Losey’s hideously made-up Trotsky resembles a superannuated Santa Claus speaking in Shakespearean tones evoking Macbeth’s “poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more.”

By contrast, Trevor Griffiths’ April 1974 contribution, “Absolute Beginners,” to the BBC TV series The Fall of Eagles contrasted the young idealistic Trotsky (Michael Kitchen) to the more pragmatic and ruthless type of organization man supposedly represented by Lenin (Patrick Stewart). “Absolute Beginners” was the jewel in a rusty crown of a series that often idealized the ruling classes. As portrayed by Kitchen, one of British television’s most distinguished character actors, Trotsky embodied a theme that runs through all of Griffiths’ work, namely, the revolutionary ideals of human brotherhood that the author counterposes to the necessity for severe political discipline, a dilemma that still remains unresolved today.

(One could add Geoffrey Rush’s Trotsky in Julie Taymor’s dreadful Frida (2002) and Ton Courtenay as a thinly disguised Trotsky in David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago (1965). Another oddity: a fictional version of the Bolshevik leader also puts in a brief appearance in W. S. Van Dyke’s Manhattan Melodrama (1934), speaking in New York City at a left-wing rally.)

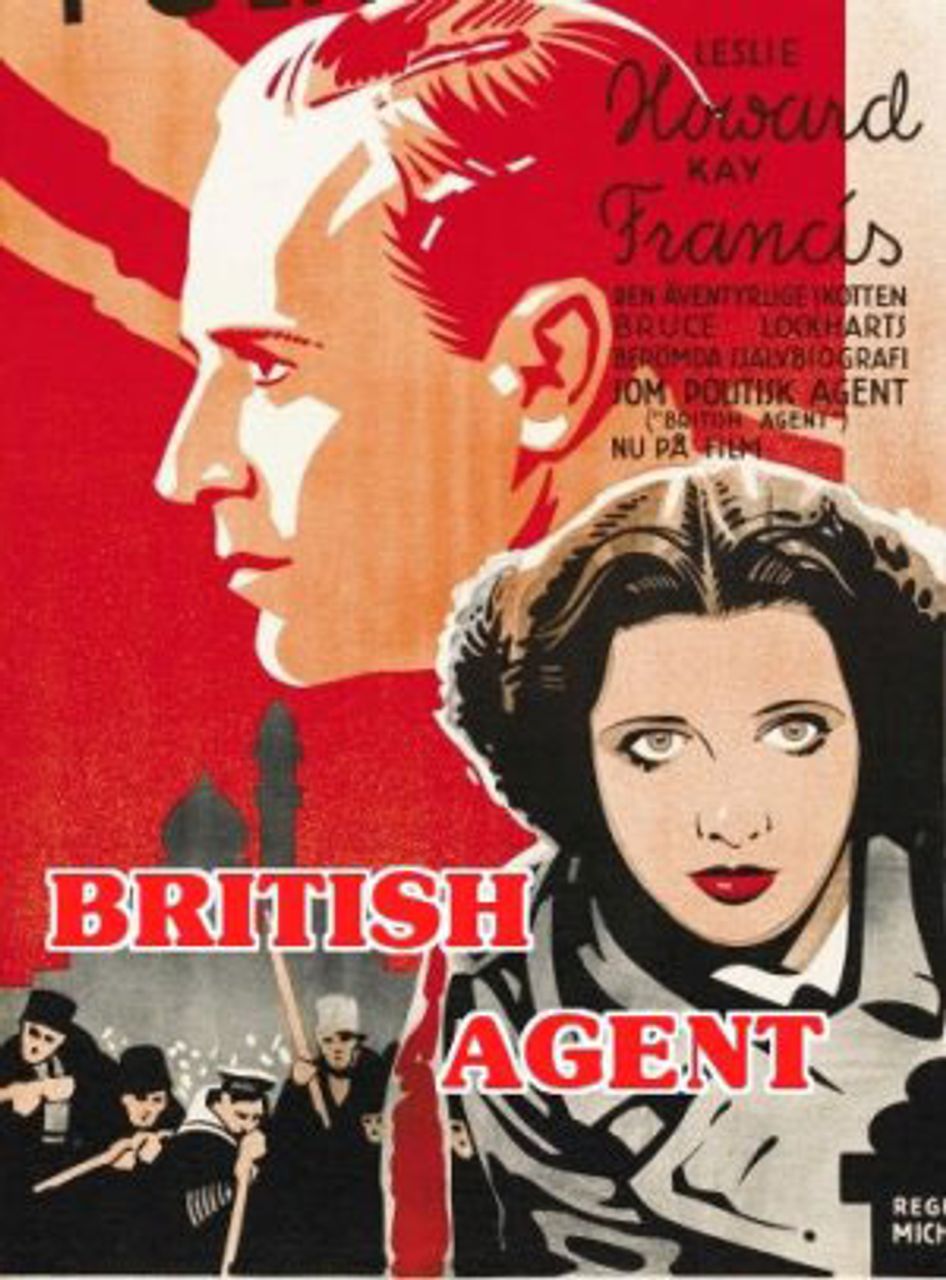

However, a long-forgotten Warner Brothers-First National production, British Agent (1934), provides a much different image of Trotsky, one closer to reality, and offers as well a revealing account of events that occurred during the first year of Bolshevik rule in Russia, including the role of British imperialism as it conspired against the revolution.

However, a long-forgotten Warner Brothers-First National production, British Agent (1934), provides a much different image of Trotsky, one closer to reality, and offers as well a revealing account of events that occurred during the first year of Bolshevik rule in Russia, including the role of British imperialism as it conspired against the revolution.

Although Trotsky only appears as a supporting player in this fictionalized film version of R.H. Bruce Lockhart’s 1932 autobiography, Memoirs of a British Agent, the depiction portrays him as neither the Nazi collaborator of the 1940s nor the pathetic old man relegated to the dustbin of history of the 1960s and 1970s. Instead, as portrayed by veteran Irish-American character actor J. Carrol Naish, this Trotsky resembles the historical original in many ways.

Several factors are responsible for this unique film, which not only treats the Russian Revolution with some degree of respect, but also unveils the devious activities of its two central characters that later historical investigations would explore. Although British Agent moves in the general realm of fictionalized Hollywood romance, it is also a Depression-era film from the one studio, Warner Brothers, that explicitly supported Roosevelt’s New Deal policies and made more of an attempt to reflect the real conditions affecting most Americans than any of its contemporaries.

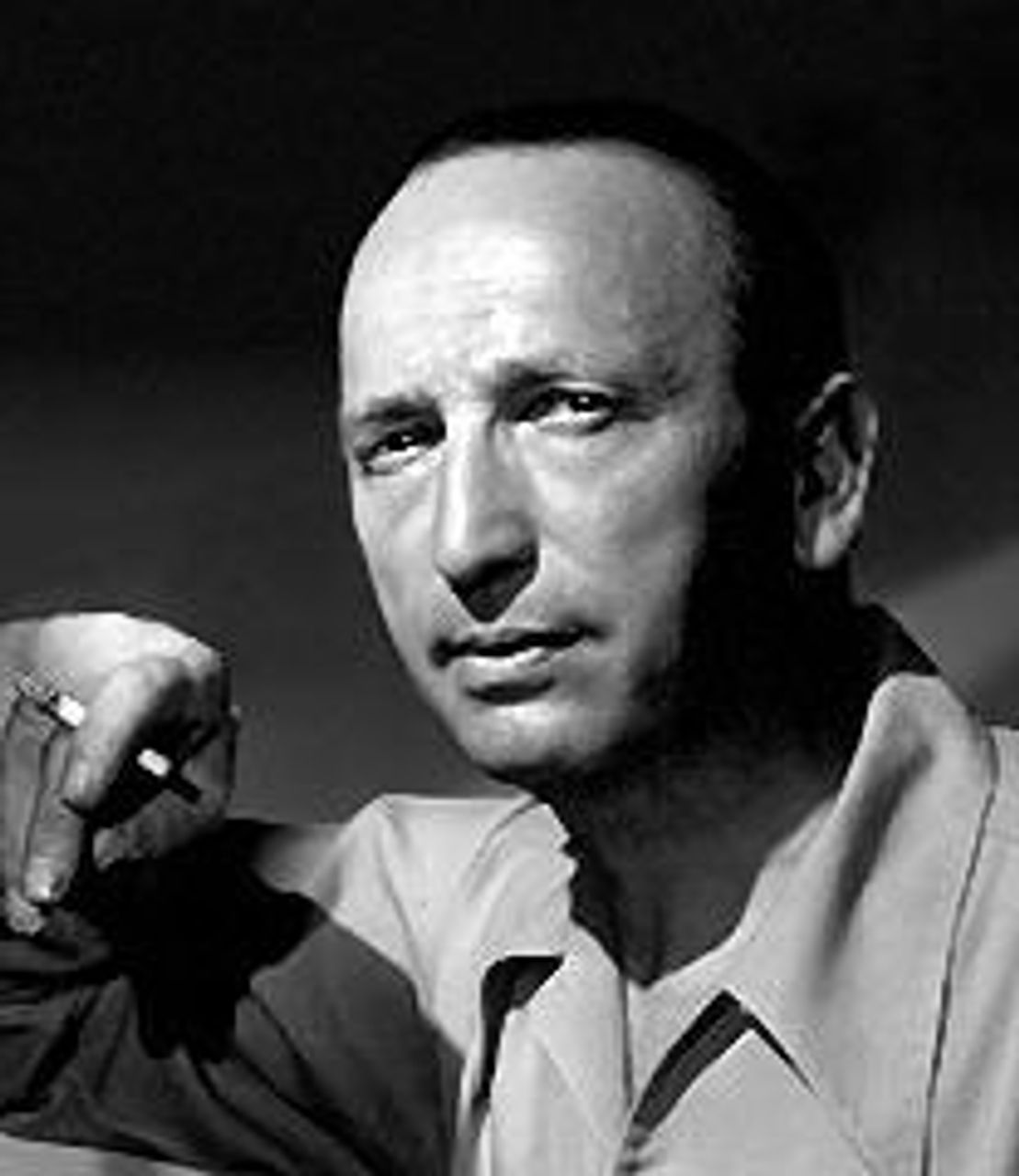

Michael Curtiz

Michael CurtizScripted by Laird Doyle, with British dialogue supplied by British writer Roland Pertwee, the film is directed by Michael Curtiz, a political refugee from the abortive Hungarian uprising of 1919, who worked in Germany, Austria, England, and Scandinavia before relocating to Hollywood in 1926. Although generally regarded as an adaptable studio director and skilled technician, Ephraim Katz notes that “certain of his [Curtiz’s] films of the 30s and 40s tend to contradict this simple assessment.”5 Along with other works such as Black Fury (1935), The Sea Hawk (1940), The Sea Wolf (1941), Casablanca (1942), Mildred Pierce (1945), Flamingo Road (1949) and The Breaking Point (1950), British Agent is one of these films.

Some films owe much to their historical moment, gaining strength from the collaboration of certain individuals and narrative trends within a given era. British Agent is a key example of this tendency. But, as well as being a studio film that could never have appeared in the Red-baiting era of the 1920s or during the Cold War, it also owes much to its revised treatment of certain leading players in the drama, such as Stephen Locke, based on R.H. Bruce Lockhart, and its heroine, Elena Moura, his love.

Leslie Howard and Kay Francis

Leslie Howard and Kay FrancisCasting Leslie Howard as Locke needs no explanation, as he was the archetypal “Brit” deployed in the 1930s Hollywood studio system, whether playing his own nationality in Of Human Bondage (1934), The Petrified Forest (1935), and Intermezzo (1939) or an aristocratic Southerner in Gone with the Wind (1939).

Kay Francis seems an odd choice to play a Bolshevik, Elena Moura. Indeed initially, Francis, known for her portrayals of stylish, worldly society ladies, appears miscast. However, such a first impression fails to do justice to both her performance and the real historical character her role is based on, namely the aristocratic lover of diplomat Lockhart in 1918, who may have been a Soviet agent, according to recent archive explorations by historian Alexander Rabinowitch.6

British Agent attempts to remain faithful to its source material. Lockhart (1887-1970) functioned as Britain’s acting consul-general in the last years of the tsarist regime and the beginning of the February Revolution in 1917. He then returned to Russia in an unofficial capacity in late January 1918 to try to persuade the new Soviet government to continue fighting Germany in World War I.

In his memoirs, Lockhart presents himself as sympathetic to the problems faced by the new workers’ state and critical of the British prime minister, the virulently anti-Bolshevik David Lloyd George. However, Lockhart offers a highly selective version of events that later led to his being named as the key conspirator in the “Lockhart Plot,” along with the notorious Sidney Reilly (“Ace of Spies”), involving the attempted assassination of Lenin in 1918. Lockhart was later sentenced to death “in absentia” were he ever to set foot in Soviet Russia again, after his release from Cheka headquarters following an exchange with London for Soviet official Maxim Litvinov.

Although Lockhart distances himself from Reilly in his memoirs, later evidence confirmed that the two were in much closer contact. As Lockhart’s son, Robin Bruce Lockhart, reveals in his book Reilly: Ace of Spies (which became the source of the 1983 Euston Films television mini-series with Sam Neill in the title role), “Reilly obtained his funds partly from Bruce Lockhart in Moscow [from June 1918].”

Although Lockhart “personally disagreed with the policy of anti-Bolshevik intervention, when he realized his views were not shared in London and that intervention was inevitable, he decided to comply with War Cabinet policy.”7 One of the later episodes of the Reilly: Ace of Spies mini-series actually shows Reilly and Lockhart (Ian Charleson) together distributing funds to anti-Bolshevik agents. Although the failed assassination attempt on Lenin by Dora Kaplan on August 31,1918 ruined Reilly’s plans to arrest and execute both Lenin and Trotsky, the head of the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky, was already aware of what was going on; he had sent his agents into the inner circle of the conspirators, and it was only a matter of time before they would have been arrested anyway.8

Nevertheless, making allowance for the self-serving nature of Lockhart’s memoirs, several interesting features of the post-October climate appear in his account. Lockhart dismissed the idea prevalent among ruling British circles that Lenin and Trotsky were really German staff officers in disguise and that the Bolshevik peace proposals to the Germans resulted merely from the prevailing war weariness.9

The Russian bourgeoisie desired the intervention of either British or German troops to overthrow Bolshevism and restore their positions and wealth. Despite some cutting remarks, Lockhart is clearly impressed with Trotsky, whom he met on February 18, 1918, and although he points to Trotsky’s bitterness toward the English, he also observes, “We had not handled Trotsky wisely.” Life in Petrograd at that point differed from what was to come in following years. The main violence in those early days came from roving bands of anarchists made up of ”robbers, ex-army officers, and adventurers.”10

Despite his identification with the British ruling class, Lockhart is honest enough to recognize the difference between what he saw in this early period and what happened later during the civil war.

“I mention this comparative tolerance of the Bolsheviks, because the cruelties which followed later were the result of the intervention of the civil war. For the intensification of that bloody struggle Allied intervention, with the false hopes it raised, was largely responsible. I do not say that a policy of abstention from interference in the internal affairs of Russia would have altered the course of the Bolshevik revolution. I do suggest that our intervention intensified the terror and increased the bloodshed.”11

Trotsky maintained a friendly attitude toward Lockhart at the time and impressed the British diplomat with one remarkable proof of his physical courage when confronting a group of sailors demanding their pay. He reminded Lockhart of the early Jewish revolutionary leader Bar Kochba, who in his struggle against the Romans prayed, “We pray thee not to assist our enemies; us Thou needst not help.”

During this time, Lockhart established friendly relationships with Soviet commissars such as Karachan, Chicherin, and Radek, who, like Lenin, were then “prepared to go a long way to secure the friendly co-operation of the Allies.” By contrast, Stalin did not impress Lockhart. “He did not seem of sufficient importance to include in my gallery of Bolshevik portraits. If he had been announced then to the assembled Party as the successor of Lenin, the delegates would have roared with laughter.” Following the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, relationships took a turn for the worse and, following a May 23 meeting, a now-suspicious Trotsky closed his door to Lockhart forever.

Lockhart began to change political and ideological course, toward participation in open counter-revolution, giving a number of reasons in his memoirs such as his unwillingness to leave his Russian lover Moura behind, and various self-serving motivations, as well as one that was probably the chief motivation—“that I lacked the moral courage to resign and take a stand which would have exposed me to the odium of the vast majority of my countrymen.”12

In his memoir Lockhart mentions that despite the fact that intervention did not occur until August 4, 1918, the period from June to August saw a deterioration of relationships between the British and the Bolsheviks as well as a tightening up of Soviet discipline, “as a result of the increased danger which now threatened them.”13 The intervention does not have the desired effect of stirring up the Russian people against the new regime. Instead, the worsening situation, Reilly’s machinations, the infiltration by Cheka agents, the murder of Bolshevik leader Uritsky, and the failed assassination of Lenin lead both to Lockhart’s arrest and to violent acts of reprisal against those (both innocent and guilty) thought responsible for Lenin’s attempted murder. Following Lenin’s recovery and the arranged exchange for Litvinov, Lockhart leaves Russia forever in late September 1918, leaving behind his lover Moura, who had also been arrested and then released by the Cheka.

Moura remains a shadowy figure in this narrative, as she does in Reilly: Ace of Spies. But evidence has recently emerged suggesting that her role was far more complex than depicted in either Lockhart’s memoirs or the 1988 biography Moura: The Dangerous Life of the Baroness Budberg, by Nina Berberova. Despite never really resolving the enigma of this mysterious character, the latter book raises the probability of her involvement with the Cheka both during the early Soviet era and later.

She was certainly knowledgeable about the activities of British naval attaché Captain Francis Cromie, who was more deeply involved in attempts to overthrow the Soviet government than Lockhart’s depiction of him in his memoirs would suggest. Moura later moved in British literary and high society circles in the 1930s, continued her friendship with Lockhart, became the lover of H.G. Wells, defended the Soviet Union in 1931, and denied that the trials that year were “faked.”14

Lockhart’s memoirs appeared in 1932. Two years later, British Agent appeared in September after a production that had begun in late March. According to a Daily Variety report of January 30, 1934, Jack Warner had authorized negotiations, which failed, with the Soviet government for permission to send a crew to Russia for location shots. This would have been the first time that a Hollywood film crew worked in the Soviet Union (perhaps the depiction of Trotsky in British Agent forestalled this possibility). Frank Borzage was originally scheduled to direct, but was replaced by Curtiz.15

Neither Lockhart nor Moura appears to have had any direct involvement in the production. However, Berberova mentions that during the early 1930s, while still acting as Maxim Gorki’s literary agent, Moura, who now had gained British citizenship, began working for both film producers Alexander Korda and J. Arthur Rank, whom Lockhart knew at a time when movies about the Soviet Union were coming into vogue.

British Agent is a remarkable film in many ways. It not only depicts the first year of the Soviet regime as a non-monolithic entity facing internal and external destabilizing forces, but also indirectly suggests that the “Lockhart Plot” was not a Soviet fabrication. Several scenes show Leslie Howard’s Locke directly engaged in promoting sabotage with his American, French, and Italian colleagues.

British Agent is a remarkable film in many ways. It not only depicts the first year of the Soviet regime as a non-monolithic entity facing internal and external destabilizing forces, but also indirectly suggests that the “Lockhart Plot” was not a Soviet fabrication. Several scenes show Leslie Howard’s Locke directly engaged in promoting sabotage with his American, French, and Italian colleagues.

Moura (now changed to Kay Francis’s Elena) is not only a Bolshevik revolutionary, but someone also employed as a secretary in the Cheka on very friendly terms with Sergei Pavlov (Irving Pichel, the future director and blacklist victim), based on the future vice-chairman of the Cheka and Revolutionary Tribunals Yakov (Jacob) Peters, who played a prominent role during the July 1918-March 1919 Red Terror while Lockhart was under arrest.

In addition to Howard and Francis, the cast includes supporting actors William Gargan as gum-chewing, wisecracking American officer Bob Medill; Phillip Reed as French diplomat LeFarge; and Cesar Romero as dashing Italian “Tito.” These character actors portray thinly disguised versions of Lockhart’s fellow Allied representatives Major Riggs, General Joseph Noulens, and General Romei.

The film opens with Howard’s Locke at a British cabinet meeting presided over by Lloyd George, who argues for the recognition of whatever government is in power in Russia to keep that country fighting on the Allied side in World War I. No date is given for this meeting, but it must occur in January 1918, after Lockhart obtained a letter of introduction from Bolshevik ambassador Litvinov to Trotsky, who was then negotiating the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Germans.

The film’s sequence of events is therefore historically inaccurate, since it has the Provisional Government still in power when it begins. Locke then returns to Russia to attend a British embassy ball on the very evening of the October Revolution (in fact, he was not in Russia at the time of the Bolshevik seizure of power). One of the guests, Kolinoff (Gregory Gaye), obviously a stand-in for Aleksandr Kerensky, assures skeptical Western ambassadors that the provisional government will make no peace with Germany and that “there will be no revolution in Russia.”

The next image is an abrupt cut of Lenin (Tenen Holz) mobilizing the revolutionary proletariat on that historical October night.

While aristocratic guests blindly ignore the realities of the emerging revolution by engaging in small talk—“Who won the Derby in 1915?”—Bolshevik-led forces march through the streets of Petrograd. Among them, Elena wears a conspicuous leather overcoat subtly suggesting Cheka connections. After she fires a shot at a Cossack beating a mother and child, she takes refuge in the grounds of the British embassy and is saved from the pursuing Cossacks by Stephen.

Despite noting their political differences, British Agent engages in the typical Hollywood romantic depiction of “love at first sight.” If Rudyard Kipling declared that the Colonel’s lady and Judy O’Grady are sisters under the skin, Hollywood’s answer is that love conquers all. It also romantically reverses Kipling’s “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet”—that is, unless they appear in a Hollywood film.

Despite noting their political differences, British Agent engages in the typical Hollywood romantic depiction of “love at first sight.” If Rudyard Kipling declared that the Colonel’s lady and Judy O’Grady are sisters under the skin, Hollywood’s answer is that love conquers all. It also romantically reverses Kipling’s “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet”—that is, unless they appear in a Hollywood film.

After Elena departs, Stephen returns inside. But by this time, revolutionary forces rally outside the embassy doors after Cossack guards have deserted. British ambassador Sir Walter Carrister orders the doors open. However, instead of the undisciplined crowd smashing shop windows in earlier scenes, Sir Walter encounters a disciplined band of revolutionaries led by an unnamed Trotsky, who announces, “We represent the Soviet Government. We have just come into power.” After learning that Kolinoff has gone to the Winter Palace, he apologizes for the intrusion, bids the dancing to continue (“if you feel like it”) and leaves with the revolutionary forces.

In this introductory scene, Trotsky appears as the leader of a disciplined proletariat over which he exercises control very much like Lenin in his first scene. He is presented neither as a Bolshevik knight in shining armor nor as a malignant revolutionary genius loci, but as someone resembling the figure described by Lockhart in his diary entry of February 12, 1918. There, the head of the American Red Cross Mission, Raymond Robins, grudgingly describes Trotsky as a “poor kind [of] son of a bitch but the greatest Jew since Christ.”16

Meanwhile, back in London, Lloyd George and his Cabinet debate the change of events and decide to make Locke their unofficial representative and deny all knowledge of his activities: “We will have nothing to do with Stephen Locke.”

Later, in a cabaret Locke sees Elena arrive in the company of Pavlov, an association that suggests not only her Cheka connections, but also a relationship that continued until the arrest and execution of the real-life Peters in 1938.17 Despite the romantic attraction between Elena and Stephen, the film also represents their ideological differences. While Elena stresses the people’s desire for “no more war,” Stephen counters her arguments with official Allied policy statements.

In a subsequent sequence, Stephen arrives at the Smolny Institute, where peace negotiations are being discussed. He requests a three-week period to communicate with London to prevent a German-Russian peace agreement. He agrees to Trotsky’s request for aid to the new Bolshevik government.

Though Stephen hopes that England will back him “if only for his reputation,” Elena is far more insightful in recognizing his character flaws. She describes him as “Clever, but not clever enough, weak, but not weak enough, strong, but not strong enough,” in terms uncannily echoing Lockhart’s own diary entries of August 2-4, 1924. Whoever contributed these lines to the film had direct access to Lockhart’s own diary, which would not be published until many decades later.18

(Although Lockhart distanced himself from the film in his diary entries, it seems likely that he may have been more closely involved. It is possible that British dialogue director/actor/playwright/screenwriter Pertwee may have contacted Lockhart for background information. These lines were clearly supplied by Lockhart himself.)

Once Stephen hears that British troops have arrived at Archangel under General Poole to overthrow the Bolsheviks and not support them, he gets over his humiliation and curt dismissal by Trotsky and engages in subversive activities to aid the White counter-revolutionary forces. His Allied friends suggest that since he has no official status, he can raise money as a” private citizen.” Without hesitation, Stephen begins to carry out many of the activities ascribed to Sidney Reilly by making contact with Lettish officer Mirov, enlisting the aid of Cadets to overthrow the Soviet government, and get Russia back into the war.

British Agent takes seriously the Soviet “Lockhart Plot” thesis long denied by the British government. During the time Locke is engaged in activities more befitting the unseen Reilly, Pavel persuades Elena to obtain evidence of her lover’s involvement with counter-revolutionary forces: “Everything must be sacrificed for the new Russia.” She feels reluctant about this, but once Dora Kaplan’s assassination attempt on Lenin occurs, she finally supplies the evidence. Pavel issues orders for a Red Terror. During this time, while Lenin is totally incapacitated, violent chaos ensues. When Red forces storm the British embassy, they shoot unarmed butler Evans (Ivan Simpson), the fictional surrogate for conspirator Captain Cromie.19

Despite his supposed “private citizen status,” Stephen’s funding of sabotage in British Agent implicitly suggests he may not be acting solely on his own, but as an agent of the British government determined to destroy the Soviet regime. It also lends substance to Trotsky’s remarks to Lockhart recorded in his diary entry for February 26, 1919: “Loud in his blame of the French and said the Allies had only helped Germany by their intrigues in Russia.”20

While the Terror continues, Locke and his Allied confederates hide out in Mirov’s apartment, which contains ammunition and explosives. One by one they leave, to be arrested and, in some cases, executed.

Unlike the real-life Lockhart, Locke is not arrested and does not face execution. Instead, he remains alone. Elena learns about his location from Bob Medill, who has been taken prisoner. Deciding to die with her lover, Elena announces that she has done her “duty to the Soviets,” recognizing that she is “too much of a woman.” However, every Hollywood film must have a happy ending. Church bells announce Lenin’s recovery. A peasant woman tells the officer in charge of firing the final fatal volley at the apartment that Lenin’s first words on recovering consciousness were “Stop the Terror.” All political prisoners are released. The final image of British Agent has Stephen and Elena leaving Moscow by train, being bidden farewell by cheery Bob, none the worse for wear.

In reality, Lockhart left Russia alone via an exchange agreement with the Soviet government. Moura remained behind, until she managed to find work with Maxim Gorki. Many years later, both attended a private screening of British Agent in London. Whatever their thoughts and feelings were, they remain unrecorded. Lockhart’s diary entry for August 6, 1934, mentions a Warner Brother press lunch to launch the film, with Curtiz and Howard present. Noting that his character is different in the film, Lockhart mentions, “I took care to dissociate myself from the picture,” and adds that, “there is still one scene to which the Foreign Office may object.”21 Was this Locke’s direct involvement in sabotage?

By contrast, Berberova records a much more ambiguous response to the screening, obviously based on Moura’s reminiscences, which can also be regarded as double-edged:

“In that emptiness, that darkness and silence, Moura relived the past, not daring to touch Lockhart’s hand, doubtless afraid that if she did she would lose him forever. It is possible that he regretted having invited her, suspecting how hard it was for her. A good film had been made of his good book, flattering his vanity, and he was happy and proud. When it was over, she hid her face from him, and once they were out on the street they went their separate ways.”22

Was this film too close to real people and actual historical events? Although Elena, like Garbo’s Ninotchka, discovers that she is really a woman at heart and no Soviet agent, in June 1931 Moura criticized Lockhart for being a journalist lackey to Lord Beaverbrook. She still supported the Soviet regime, suggesting that, unlike Elena, she had not completely “done her duty to the Soviets.”23

British Agent concludes with the traditional Hollywood happy ending. Although historically inaccurate, as the real Moura did not leave with Lockhart, this ending contains elements of dark ambiguity unique in a Hollywood film of this period. Two complicated individuals survive at the end of the film. One is a saboteur whom the Soviet government could have legally executed, the other a heroine whose espionage activities will continue later. They leave a Soviet Union where Lenin still remains in control to stop the spread of violence that Stalin would later use as a political weapon against those who made the revolution, and where Trotsky still maintains his sincere revolutionary ideals until other circumstances will prevent him and his supporters from demonstrating what the alternative could have been in the Soviet Union.

British Agent is no accurate historical work, but a film containing certain significant elements revealing that events were not unfolding the way the British establishment meant them to be understood. Lockhart and Moura remained friends for the rest of their lives, but the film featuring them as two leading characters also contains suggestions of far darker political motivations during the first year of Bolshevik rule.

Notes

1. The Erskine Caldwell treatment of Mission to Moscow August 21, 1942. Mission to Moscow. Edited with an introduction by David Culbert. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1980, 237.

2. Mission to Moscow, 162.

3. Ibid.

4. Mission to Moscow, 163.

5. Ephraim Katz, The International Film Encyclopedia. London: Macmillan, 1982, 294. One recent attempt at assessing the complex nature of the authorial role of Michael Curtiz was made by Peter Wollen in “The Auteur Theory: Michael Curtiz and Casablanca” in Authorship and Film, edited by David A. Gerstner and Janet Staiger; New York: Routledge, 2003, 61-76. Citing a communication by Jonathan Kuntz, Wollen mentions that, “Curtiz’s characters are driven by conflicts tearing them apart. On the one hand, the character needs ‘to pretend to be uncaring and unemotional’ and on the other, feels ‘the desire for true action to right an unjust world.’” (66) In British Agent, by contrast, Moura tends to be romantically attached to Locke but is also acting for the Soviet cause. The contrast with Casablanca is the focus of Wollen’s essay. Moura decides to choose love over duty, unlike Rick Blane in the later film. Thus, British Agent ends in a typical Hollywood romantic fashion. However, in view of what we now know about the real-life heroine’s later activities, there is also the possibility that Curtiz viewed this ending ironically, taking “special trouble to cash” in on a certain moment in this film for its “maximum dramatic value.” (67). Wollen does not discuss British Agent in his essay, but it is nonetheless an interesting case study, not only in terms of the complex nature of Curtiz’s role as an auteur, but also for its historical implications.

6. Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks in Power; Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007, 157. According to p. 425, n.10, the source for this information comes from the Sidney Reilly Collection at the Hoover Institution. Although he never appears in British Agent, the role of Sidney Reilly was a key one during 1918.

7. Robin Bruce Lockhart, Reilly: Ace of Spies; London: Penguin Books, 1967, 88, 89. For Lockhart’s actual involvement in the “plot” named after him, see Richard K. Debo, “Lockhart Plot or Dzerzhinski Plot?” The Journal of Modern History 43.3 (1971): 413-439. Debo not only concludes that “little confidence can be placed in Lockhart’s memoir account of his activities” (418) when compared to evidence in the British archives, but also that he denied any participation in Reilly’s plot to overthrow the Soviet government, although he undoubtedly knew about it. Lockhart “was already considered to be a mercurial and unstable upstart by the permanent officers of the Foreign Office; a candid admission of conspiracy to commit premeditated murder would certainly have ended his career in the foreign office.” (420) For recent confirmation of Lockhart’s involvement, see also Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd; Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2007, 319, 338; Mike Thomson, “Did Britain try to assassinate Lenin?” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-12785695. The last article cites a recently discovered letter by Robin Lockhart that states his father worked “much more closely with Reilly than he had publicly indicated….”

8. Op. cit. 188-189. Other sources suggest that Communist sympathizer and Le Figaro journalist Rene Marchand betrayed them. On his return to England, Lockhart (since Reilly could not be named for security reasons) received a stinging rebuke from Liberal M.P. Joseph King in the House of Commons, who also “made a violent attack on the Government’s whole policy towards Russia and on the misuse of Secret Service funds.” Op. cit, 104.

9. R.H. Bruce Lockhart, Memoirs of a British Agent, London: Macmillan, 1974. 197.

10. Op. cit., 213, 226, 241-242.

11. Op. cit., 242.

12. Op cit., 253-254, 257, 289.

13. Op. cit., 290.

14. See Nina Berberova, Moura: The Dangerous Life of the Baroness Budberg; Translated by Marian Schwartz and Richard D. Sylvester; New York: The New York Review of Books, 2005, 210-211. Moura played a mysterious role in making a secret trip to Moscow ostensibly to return private archives to Maxim Gorki (material that would have been valuable to Stalin in the forthcoming purges). Although Berberova suggests that Gorki wanted the return of his archives to save someone close to him from the forthcoming purges, this explanation appears weak in light of the fact that Yagoda had already planted someone in Gorki’s employ to spy on the writer’s changing moods. The return of the manuscripts sounds suspiciously like a Cheka plot, as Gorki never again saw those archives. See Berberova, 248-254. From the 1930s to the early 1950s, Moura had also attempted to attract Soviet writers into the International Pen Club, now chaired by H.G. Wells, while barring Russian émigré writers from membership. Op. cit.255-256, n 1. Although Berberova reserves judgment on this matter and other dubious activities of Moura, she does cite an interesting footnote mentioning a suspicion that 1930s Parisian literary circles had about certain Russian women who had married French artistic celebrities: “One always had the feeling on making their acquaintance that they had probably been sent by Moscow to attach themselves to these celebrities, with the principal mission of keeping these men of genius under Stalin’s influence and preventing them from expressing critical opinions about him or changing their political position.” See op. cit, 241, n. 7.

15. See The American Film Institute Catalog: Feature Films, 1931-1940. Film Entries A-L; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, 237.

16. Op. cit., 33.

17. Berberova notes that until 1938, “Moura still had some rather durable ties to someone high up in the Soviet diplomatic hierarchy or the NKVD…” (290), but she does not identify the source. During Lockhart’s arrest in 1918, despite her own arrest and release, Moura seems to have been on very friendly terms with Peters, who had been involved in the 1911 London siege of Sidney Street. See 62-63, 75-78. See also The Diaries of Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, 44-45. In his 1925 article, “Memoirs of Cheka Work during the First Year of the Revolution,” Peters mentioned that Moura “had been a German spy during the imperialist war.” See Berberova, p. 128, n. 1. During an episode of Reilly: Ace of Spies, Sam Neill’s Sidney Reilly mentions Moura’s pre-war German associations. For further evidence of Moura’s Cheka connections, see also Richard B. Spence, Trust No One: The Secret World of Sidney Reilly; Los Angeles: Feral House, 2002, 193, 202, 213, 222, 224, 233, 457, 479.

18. “She despises me for not throwing over everything and taking my courage in both hands, but the truth is that even if everything were favorable and there were no obstacles and no obligations I should not want to do it.” The Diaries of Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart: Volume One—1915-1938; Edited by Kenneth Young; London: Macmillan, 1973. 58. See also Berberova, 186-191, who not only provides a more detailed account of this meeting but also questions Moura’s claim to have translated six of Gorki’s works between 1921 and 1924, when, in fact, only one had appeared. Also, despite her aristocratic background, Moura predicts the success of world revolution to Lockhart and says that the capitalists should recognize the inevitable. See Berberova, 190. Lockhart’s diary entries for August 2-4, 1924, read as follows: “Moura says I am a little strong, but not strong enough, a little clever, but not clever enough, and a little weak, but not weak enough.” Diaries, 58-59.

19. For Cromie’s involvement in counter-revolutionary activities, see Robin Bruce Lockhart, Reilly: Ace of Spies, 186-188; Debo, 430-431; Rabinowitch, 156-157, 321-323, 337-338.

20. Diaries, 33.

21. Diaries, 300.

22. Berberova, 208.

23. Berberova, 209.

The author wishes to thank David Walsh for his editorial suggestions and additions.