Grain prices surged to new records after the US Department of Agriculture downgraded its harvest projections. The corn crop is now expected to be 10.8 billion bushels, 13 percent less than last year’s harvest.

Initially the USDA had estimated the 2012 corn crop would be the largest since 1937, with 94.6 million acres planted. After months of severe drought and the hottest year on record, however, the agency on Friday reported that cornfields would yield an average of 123.4 bushels per acre, the lowest yield in 17 years.

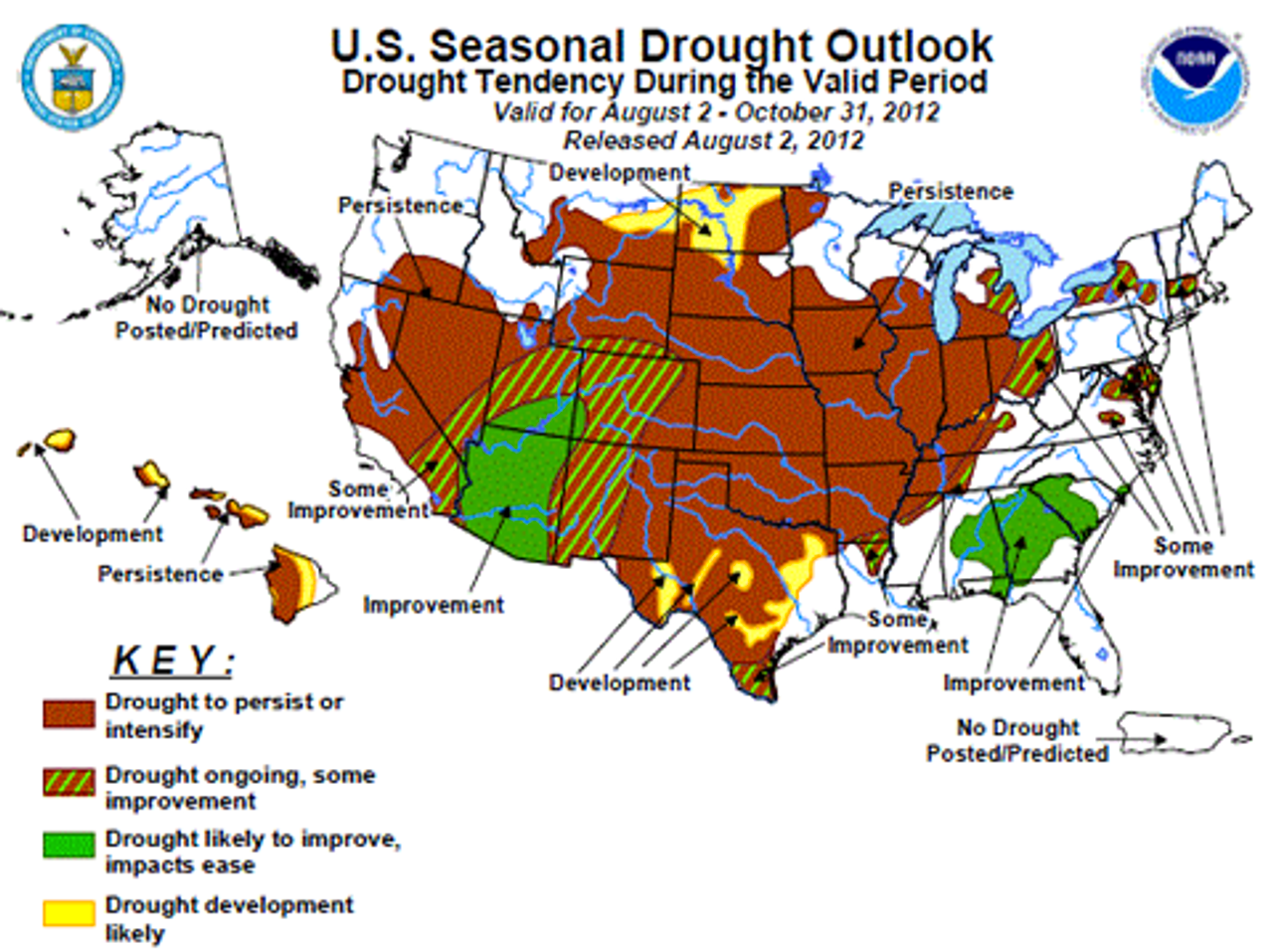

The US is the world’s leading producer of corn, soybeans, and wheat, accounting for one in every three bushels traded globally. The National Weather Service forecasts that drought conditions—the most severe in more than half a century—will persist through the end of October, posing the threat of soil damage and water depletion that will carry over into the next growing season.

Corn for December delivery shot up on the bad news on the Chicago Board of Trade Friday to a record $8.49 a bushel, before dropping back to $7.89 on Monday. Prices for other grains also spiked and then slid back slightly, with traders expressing disappointment over improved weather and “smaller-than-expected cuts in global wheat production.”

“It is a little bit of profit-taking today and we are seeing a bit of buy-the-rumour and sell-the-fact scenario,” a commodities strategist for the Commonwealth Bank of Australia commented to Reuters. “The fundamental picture is very bullish as the US and global corn supplies are critically tight.”

In July, global food prices rose 6.2 percent, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization reported last week. The FAO attributed the spike primarily to the rise in corn prices, which have soared by 60 percent in the past two months. The organization’s cereal index rose 17 percent in July, to a level approaching the all-time high reached in April 2008. Food inflation that year precipitated food protests worldwide and pushed 100 million people into hunger. (See “Spiking grain prices raise specter of global food crisis”)

On Monday, the USDA reported that 51 percent of the corn crop was in “poor” or “very poor” condition. Only 23 percent was considered “good” or “excellent.”

Many farmers in key corn producing states of Indiana and Illinois have reported total crop loss. Even in less devastated areas, farmers have reported yields substantially lower than the government estimates. “We’ve lost 60 percent of our average production, if not 70,” Johnson County, Kansas Farm Bureau president Nick Guetterman told the New York Times.

Rain and cooler temperatures across the Midwest minimally improved the potential for soybean crops, 38 percent of which are currently listed in the worst condition. For the earlier-harvested corn, the moderate weather will do little to improve yields. “Some of those fields that were going to be good will be good now until harvest,” USDA statistics director Greg Thessen told the Associated Press. “For others, there’s not a lot further down it could go.”

Soybeans could see some improvement in bean size within the pods from the rain, but it is too late in the season for plants to produce more pods. “If we keep close to normal temperatures and get some rain, it probably would have a little impact on soybeans, but how much is yet to be determined,” Thessen said, adding, “the drought’s certainly not over.” For the year, rainfall remains far below average.

The USDA has projected that domestic inventories of soybeans will drop to 115 million bushels, the lowest level in nine years and second lowest since 1973.

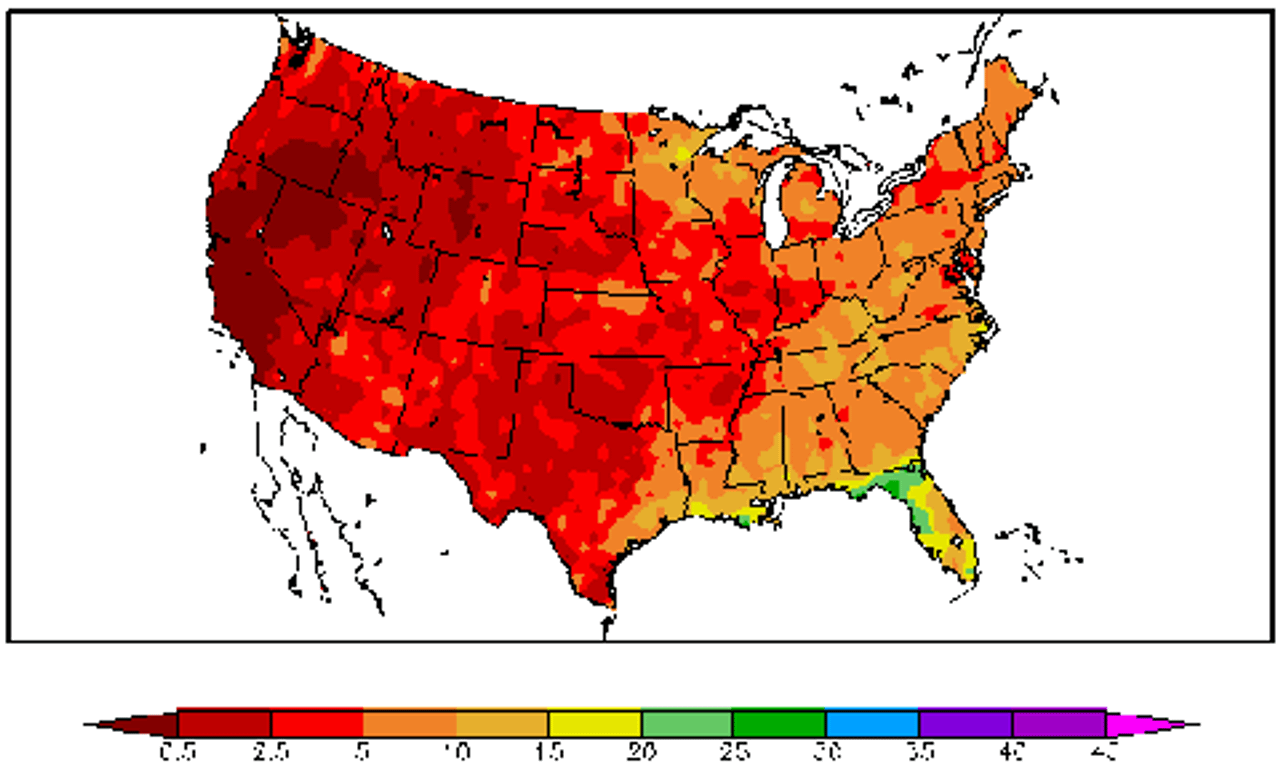

Precipitation in inches, June 15 - August 13. Source: Regional Climate Centers, National Drought Monitor.

Precipitation in inches, June 15 - August 13. Source: Regional Climate Centers, National Drought Monitor.In issuing its August 9 report, the FAO cautioned that importer countries must prepare “contingency plans” against the social upheavals. “The phenomenon of high and volatile food prices is unlikely to disappear any time soon,” the agency stated. Thirty countries are considered “high risk due to food prices” because of the high numbers of urban poor, landless laborers, refugees, and others living in absolute poverty. For billions of the world’s poor, food is the largest expense families confront.

“The real problem is this is the third price shock in the last five years,” UN World Food Program analyst Arif Husain told the New York Times. “The poorer countries haven’t had time to recover from previous crises.” Across northern Africa, grain prices have pushed the poorest populations to the brink. “There are a number of reactions” to price increases, Eric Hazard of Oxfam in Senegal noted. “People diminish the number of meals, and the quality of their meals. We’ve seen an increase in migration.”

Like the US corn belt, key agricultural regions in Russia, India, Australia and South America have also sustained damage from extreme weather. The Russian wheat crop, heavily depended upon by import countries of the Middle East and North Africa, has been downgraded to a level just above the average amount consumed domestically. The outlook has raised fears that Russia will resort to an export ban like that which fueled a food crisis in 2010 and fed into uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt and elsewhere.

As the FAO issued its warning, the organization’s director general, José Graziano da Silva, commented in the Financial Times that “Countries and the UN are better equipped than in 2007-08 to face high food prices.”

In fact, with none of the problems that underlay the previous shocks resolved, world governments and organizations are in a state of paralysis over how to manage the next crisis. Speculation, led by major banks and hedge funds, is expected to drive corn to $9 or even $10 per bushel and soybeans to $20 by year’s end. Traders are seizing on the worsening climate disaster to invest not only in crop futures but also in water supplies and arable land.

National governments have made clear they reserve the right to erect trade barriers. Russian Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich responded to last week’s reports by saying only that he saw no grounds for an immediate wheat export ban, but would not rule out such a measure at the end of the year.

China, the world’s prime importer of soybeans, has said it would release some government corn and rice reserves for domestic use to tide the country over for the next few months. Bangladesh announced Thursday that it would not export rice until at least June.

FAO’s da Silva urged the US government to suspend its federal ethanol mandate, which effectively guarantees 40 percent of the domestic corn crop to fuel producers. The impact of high corn feed prices and drought-ruined pastureland has compelled many livestock producers to slaughter their herds. The situation poses rising inflation in the coming months for meat, dairy and poultry products.

The Obama administration, seeking to quell discontent during the election season, has downplayed the risk of consumer inflation and promised a pittance to ranchers, who are not insured by the USDA. On Monday, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack announced that the USDA would purchase up to $170 million in pork, chicken, fish and other meats. Most of the money ($100 million) will go to large pork producers. Estimated losses in the livestock industry are already an order of magnitude more than the amount of aid promised. A likely consequence of the disaster is a massive consolidation of the meat industry, benefiting only the biggest corporations.

In an interview on C-Span’s “Newsmakers” program, Vilsack insisted, “American farmers are a resilient bunch. They will get through this.”

France, Mexico, and the US have announced a conference call scheduled at the end of August to discuss whether to convene an emergency meeting of the G20’s “Rapid Response Forum” over the rising food prices and threats of protectionism. The body has no power to impose binding decisions on member states, let alone regulate the commodities market speculation that is behind the extreme price volatility.