Global food prices rose 6.2 percent in July, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization reported Thursday. The FAO said it released its Food Price Index ahead of its regular publication schedule as a warning against the impact of such price rises.

The index, which calculates the cost of a basket of food commodities, overall averaged 213 points in July, up 12 points from June. In February 2011, the height of the Arab Spring, the overall index peaked at 238. The index has remained above the average 2008 level for more than a year and is now trending toward an all-time high.

Grain prices have driven the overall rise. The US corn crop is in a state of disaster, with more than half of all US acreage listed in poor or very poor condition due to a record-breaking drought. Under a parallel drought, Russia downgraded its wheat crop by several million tons on Wednesday.

The FAO cereal index averaged 260 points in July, up 17 percent over the month. Most of the increase is attributable to a 23 percent rise in corn prices over the month and a similar, 19 percent surge in wheat prices. The cereal index is only 14 points below the all-time high of 274 points in April 2008.

The FAO registered a 12 percent rise in sugar prices in July, triggered by unseasonably wet weather in Brazil, the world’s largest exporter of cane sugar. Oils rose 2 percent, primarily on tighter supply outlooks and record prices for soybeans.

Price indexes for meats and dairy remained relatively unchanged for the month, although the protracted drought in the US rangeland has distressed many ranchers, who will be compelled to liquidate their herds. The US Department of Agriculture projects US consumer price inflation for meat, poultry, and dairy in the next few months as a result. Internationally, the higher cost of animal feed will ripple through livestock producers. This process may sharply affect Asia, where demand for meat is growing, but nations have smaller domestic stockpiles.

International food organization Oxfam warned in response to the FAO report that “millions of the world’s poorest will face devastation” from the increases. “This is not some gentle monthly wake-up call—it’s the same global alarm that’s been screaming at us since 2008,” Oxfam spokesman Colin Roche stated. “These figures prove that the world’s food system cannot cope on crumbling foundations. The combination of rising prices and expected low reserves means the world is facing a double danger.”

One billion people suffer from hunger worldwide. Hundreds of millions more who live in poverty are vulnerable to food inflation because they spend half or more of their incomes on staple goods. Food price shocks in 2008—driven by a confluence of weather disasters, protectionist measures, and speculators jumping ship from the financial market into commodities—produced food protests across more than 30 countries.

“There is a potential for a situation to develop like we had back in 2007-08,” FAO economist and grain analyst Abdolreza Abbassian told Reuters Thursday. “There is an expectation that this time around we will not pursue bad policies and intervene in the market by restrictions, and if that doesn’t happen we will not see such a serious situation as 2007/08. But if those policies get repeated, anything is possible.”

While economists and aid organizations have issued progressively dire warnings over the consequences of another food crisis, the underlying factors—extreme weather, a disjointed food distribution system, the possibility of export bans, and above all, rampant speculation—are more exacerbated than ever.

Indeed, commodities investors have rallied on the raft of bad news, making price shocks inevitable. Traders on the Chicago Board of Trade, banking on the USDA to issue a dire outlook on Friday, sent corn prices soaring Thursday morning to $8.265 per bushel, two cents below the all-time record set in July.

Major banks and hedge funds in particular have played a role in the rally. As Bloomberg News noted, “crops are the best-performing commodities this year, and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Macquarie Group Ltd. and Credit Suisse Group AG say the trend will continue.”

One Chicago trader commented to Reuters that Goldman Sachs was leading the betting on a USDA corn yield downgrade and predicting $9 corn and $20 soybeans by November. “The Goldman roll started Tuesday, you have that going on and the report is tomorrow. Everyone is expecting the corn number to be pretty friendly.”

Jaime Miralles of investment firm Intl FC Stone Europe said that “a firm $9 corn sentiment remains as rationing is and will be required.” Other speculators anticipate $10 per bushel corn prices in the coming months.

“I think general price firmness is being seen in ahead of the USDA report because the market is increasingly realising how horrible conditions are for U.S. corn,” Rabobank analyst Erin FitzPatrick commented. “There is pre-positioning ahead of the report as people are expecting more cuts in US harvest forecasts. Despite recent rain in the US, a lot of the damage has already been done to corn.”

Farmers and agricultural economists estimate that corn yield in much of the Corn Belt will be far lower than the USDA’s already downgraded estimate of 146 bushels per acre. Some areas may yield 100 bushels per acre or less, knocking the national corn crop back to levels not seen in decades.

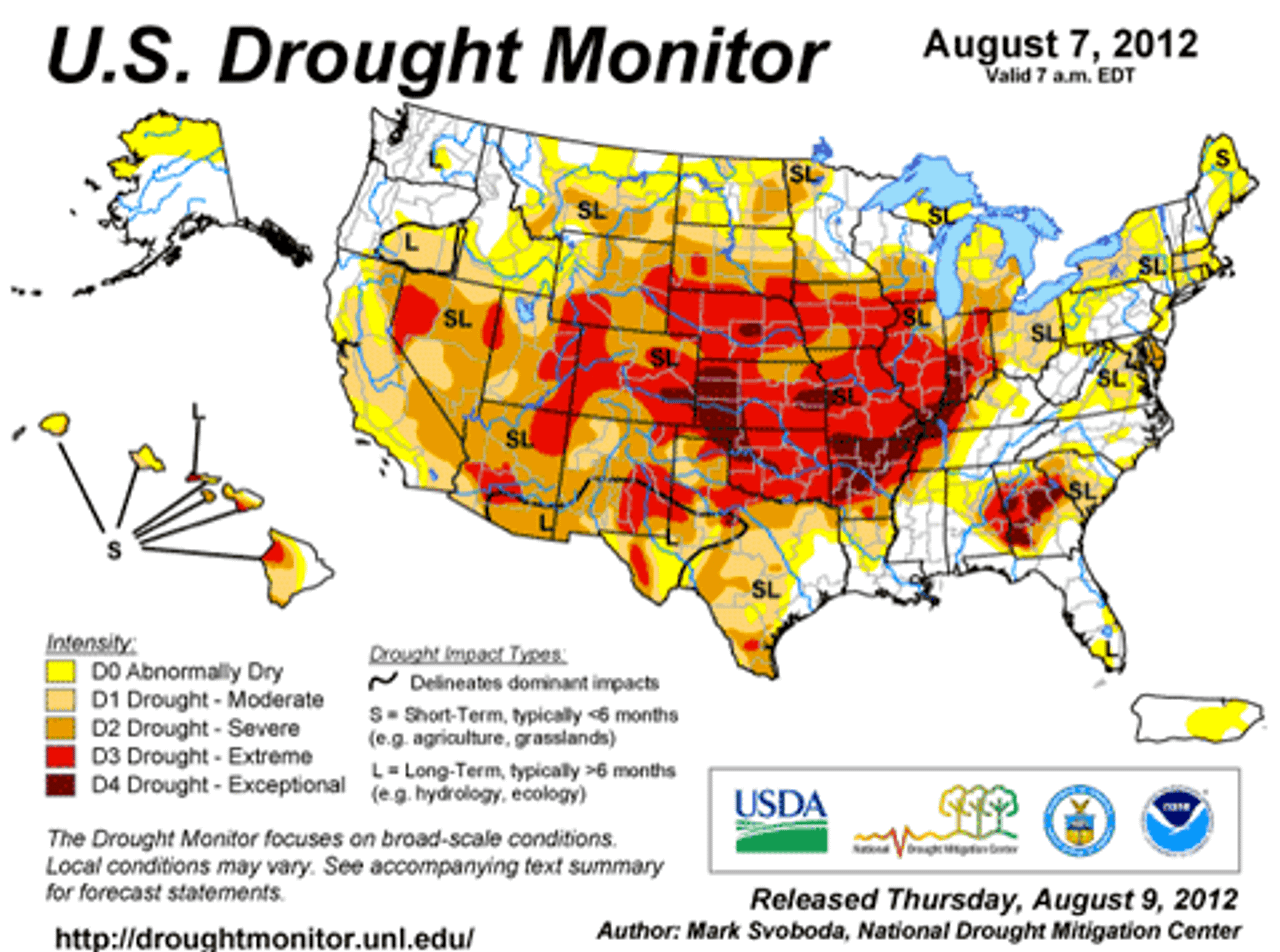

The US Drought Monitor reported that for the week ending August 7, fully 80 percent of the contiguous US is experiencing drought. “Every day we go without significant rain is tightening the noose,” said meteorologist Mark Svoboda, who authored the latest Monitor report. In Iowa, the largest corn producing state, the area suffering from extreme drought more than doubled in size. As of August 7, nearly 70 percent of the state was under the most severe category of drought. Over 81 percent of Illinois and fully 94 percent of Missouri is in “at least extreme drought.”

The US Drought Monitor reported that for the week ending August 7, fully 80 percent of the contiguous US is experiencing drought. “Every day we go without significant rain is tightening the noose,” said meteorologist Mark Svoboda, who authored the latest Monitor report. In Iowa, the largest corn producing state, the area suffering from extreme drought more than doubled in size. As of August 7, nearly 70 percent of the state was under the most severe category of drought. Over 81 percent of Illinois and fully 94 percent of Missouri is in “at least extreme drought.”

The USDA estimates that inventories of corn, wheat, soybeans, and rice will be reduced to 2008 levels next year. Wheat inventories are projected to contract 7.5 percent.

Wheat production in Russia, the fourth largest exporter, is set to fall by 20 percent this year. The Australian wheat crop, stunted by repeated frosts and poor weather, may yield 40 percent less than initial projections. India’s agricultural region suffered a monsoon season providing 22 percent less rainfall than average, resulting in a 7.8 million ton loss in the global rice crop. The FAO also reduced rice production forecasts for Cambodia, Taiwan, North and South Korea, and Nepal.