PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

From the 1870s through the 1930s the class struggle in the United States was exceptionally violent. Capitalists enforced their prerogative through brute force, crushing strikes and unions with legions of spies and hired thugs. Standing behind these private armies were the armed men of the state—police, state militia and federal troops—readily deployed by the elected officials of both the Republican and Democratic Party. Workers fought back, frequently making America’s mine, mill, and factory towns and neighborhoods the settings for pitched battles.

Among the bloodiest struggle of this period, the Colorado coalminers’ strike of 1913-14 stands out both for the savagery of the coal barons and the militancy and solidarity of the workers. The strike is infamous for the Ludlow massacre, in which state militia opened fire on a tent city of evicted miners and their families, killing 19. In the aftermath, miners took up arms and for 10 days exacted military-style revenge on the mine operators, the National Guard, and the right-wing bands of vigilantes that played a major part in terrorizing miners for the duration of the strike.

The strike holds important lessons for workers today, when the American ruling class has torn to shreds the social contract that softened the class struggle from the end of World War II until the 1970s. Once again workers face grim working conditions, poverty wages, and the prospect of an insecure retirement. Once again capitalists and the government are prepared to rule through violence.

The falsity of the claim that there is no history of class struggle in the United States is demonstrated by events like the Colorado miners’ strike. However, while in American history one finds no shortage of workers’ fighting against their bosses in the streets, their struggle to emancipate themselves politically lags far behind. In the strike of 1913-1914, workers faced not just the most powerful capitalist in the nation in John D. Rockefeller, Jr., but the violence of the state mobilized by Democratic Party Governor Elias Ammons.

Conditions in Colorado’s coal mines and camps

Miners were paid starvation wages to work 10 to 12-hour shifts hundreds of feet under the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. They were often forced to pay for their own mining equipment—including picks, gunpowder and dangerous open-flame head lights, which were known to cause explosions. Such blasts could kill or maim dozens of workers at a time. Explosions and cave-ins were common. Between 1884 and 1914, nearly 1,700 miners were killed in the mines. Companies rarely paid compensation to the widows and children of miners killed in accidents.

Workers were frequently robbed of wages by mine supervisors responsible for “weighing out” the coal collected during a shift. Company managers instructed supervisors to “scale slight” the miners, and workers were often suspended or fired on-the-spot for protesting. If a miner’s load included non-coal rocks, the miner was subject to fines, suspension and dismissal. Workers were also not paid for the non-mining work they were forced to perform for the companies. These included backbreaking tasks like timbering, laying railroad, and cleaning mine property.

Workers, the majority of whom were immigrants, were only paid an average of $3-4 per day—sometimes not enough to feed their families, who were usually forced to live in “closed” company towns where barbed wire lined the tops of exterior fences. The company towns were “feudal domains with the company acting as lord and master. The ‘law’ consisted of company rules. Curfews were imposed, company guards—brutal thugs armed with machine guns and rifles loaded with soft-point bullets—would not admit any ‘suspicious stranger’ into the camp and would not permit any miner to leave,” according to historian Phillip Foner.

It was common for 20 people to share a four-room company-owned shack made of discarded timber slabs. Though companies eventually replaced some of these hovels with somewhat larger boarding houses, they claimed that many of the miners preferred living in shacks, ostensibly because it reminded them of the conditions from which they fled in their countries of origin. Many companies provided no trash dumping services, and so backyards and streets were strewn with piles of garbage and rotting food.

In company towns, miners were usually forced to shop at company stores either by convenience or by threat of dismissal. In lieu of cash payment, workers were sometimes given company scrip. Scrip could only be redeemed at company stores, which usuriously charged high prices for basic food products and other necessities. At some companies, miners were given $1 per month for medical attention, which they could only redeem with a company doctor.

The Colorado Labor Wars of 1903-04

In 1902, the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) boasted 17,000 members in the coal mines of Colorado. The union had gained prominence in strikes at Cripple Creek in 1894 and Cour d’Alene in 1899. Though the WFM won workers the right to an 8-hour workday in the Cripple Creek strike, mine operators hardly ever adhered to this in the subsequent decades. The 1899 strike in Idaho was crushed when President William McKinley sent in the US Army, imprisoned 1,000 striking miners and killed a handful.

Big Bill Haywood

Big Bill Haywood

Several WFM organizers, including “Big” Bill Haywood, lost faith in the American Federation of Labor’s (AFL) method of craft unionism, which split workers in the same workplaces along lines of skill. They began to organize the WFM along the lines of industrial unionism, which sought to organize all workers in one industry into the same union.

Attacking AFL head Samuel Gompers for his betrayal of the Pullman Strike of 1894 in which he stamped out growing calls for a general strike, Haywood rose to second in command of the WFM and heeded the revolutionary sentiments of the union’s members. At the WFM convention in 1901, workers agreed to a proclamation that read: “A complete revolution of social and economic conditions is the only salvation of the working class.” The WFM would go on to help form the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905.

Colorado voters overwhelmingly approved an 8-hour workday amendment to the state constitution, with 72 percent of the vote in the 1902 elections. Though public sentiment was widely in favor of advancing the cause of the workers, the Colorado state government simply refused to implement the law.

Conditions for strike action were ripe. When in 1903 a mine explosion in Idaho Springs killed several workers, mine operators instructed the police to round up and expel all WFM organizers.

On February 14 that year, the mill workers of Colorado City—a crucial ore refinery town—walked off the job in protest of the United States Reduction and Refining Company’s refusal to meet their demands. The company had brought in agents from the Pinkerton Agency and fired 42 workers that had joined the union. The strike spread quickly as other mill owners refused to negotiate with the WFM.

After the strike began to spread, Republican Governor James Peabody sent 300 Colorado national guardsmen to Colorado City to guide scabs to work, raid the homes of workers, and terrorize organizers and their families. Six hundred national guardsmen were also ordered to guard mines in Telluride and Cripple Creek, despite the protests of hundreds of local residents.

As 3,500 workers at mines that supplied USRRC mills went on strike, elites in the Cripple Creek region formed the Cripple Creek District Citizen’s Alliance and the Cripple Creek Mine Owners’ Association to extra-legally suppress the workers’ movement.

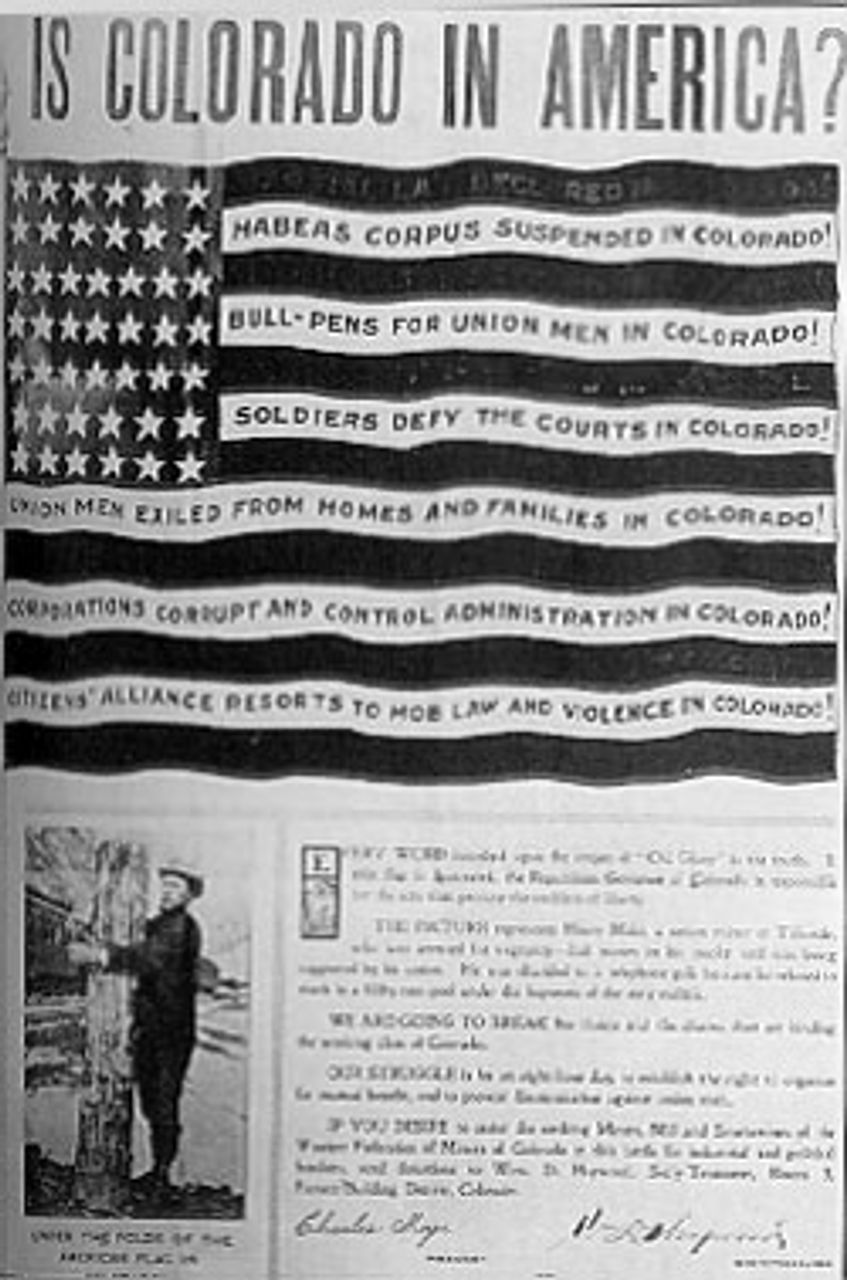

The organizations arranged for 1,000 rifles and 60,000 rounds of ammunition to be sent to Cripple Creek to be used by vigilante groups established as a tool to terrorize striking workers and their families. When vigilantes tied one worker—Henry Maki—to a telegraph pole, a photograph of the incident was used by Bill Haywood on a widely popular broadside called, “Is Colorado in America?”

A WFM broadside published by Haywood

A WFM broadside published by Haywood

The commander of the Colorado National Guard, General Sherman Bell, proclaimed that his presence was “a military necessity, which recognizes no laws, either civil or social.” Bell was particularly blunt about his goal. “I came to do up this damned anarchistic Federation [The WFM].” When asked about the National Guard’s lack of respect for due process when dealing with captured union workers, Bell responded, “Habeas corpus be damned! We’ll give ‘em post-mortems!”

On January 26, 1904, tragedy struck at the Independence Mine in Victor, Colorado, as 15 non-union, replacement workers were killed when a cable snapped and a cage used to transport miners fell 1,500 feet. All 168 men at the mine promptly walked off the job. The strike continued to grow, and the vigilantes and guard stepped up their efforts to wipe out the workers’ movement.

On June 6, an explosion at Independence mine killed 13 more miners. Fearing the mass mobilization of workers in response to the incident, mine owners removed all local officials sympathetic to workers. A sheriff who initially refused to resign was threatened with murder, prompting his departure.

On June 7, mine owners were deputized. The wave of terror that ensued swept the workers’ movement off of its feet. The Citizens Alliance vigilantes rounded up 175 workers and sympathizers and locked them in cages with no food. All told 1,569 workers and sympathizers were arrested during the strike. The Citizens Alliance established a kangaroo court and deported 230 union organizers who failed to denounce the WFM. Around this time, the National Guard surrounded WFM headquarters and fired through the windows, killing four.

On June 8, General Bell attacked a camp of union workers and killed one. Armed company agents then assaulted the local WFM newspaper, the Victor Daily Record. The press was salvaged and turned into an anti-union newspaper.

As writer George Suggs points out, “at no time did the WFM engage in armed resistance… even when their extreme harassment and provocation might have justified it.”

The strike was defeated and the WFM crushed. A large festival was held for Governor Peabody. Dubbed the “Law and Order Banquet,” the railroads offered half price tickets for Citizens Alliance members travelling to attend the event. Governor Peabody said that the crushing of the strike movement was an issue of “controlling the lawless classes.”

Although the workers were defeated in 1904, the conditions that had caused them to rise up did not improve. It was only a matter of time before tensions boiled over again.

To be continued